Intel is trying to rebuild the plane in mid-air. Since March, when longtime chip executive Lip-Bu Tan took the helm, the company has been in a rolling reset—reshuffling top jobs, rethinking how much to spend on its next manufacturing node, and striking an extraordinary pact with Washington that could make the U.S. government one of its largest shareholders. This week’s executive shake-up—products chief Michelle Johnston Holthaus is departing as Intel creates a new Central Engineering group tasked with building a custom-silicon business—underscores the urgency. The message from the new regime is blunt: fewer layers, faster decisions, and designs that satisfy external customers as much as Intel’s own product teams.

At the center of it all is a manufacturing bet Intel calls 18A, the process technology meant to prove the company can still compete with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. Intel has talked up 18A all year, promising first products in late 2025. But behind the scenes, yields have lagged expectations, forcing schedule triage on the first 18A laptop chips, code-named Panther Lake, and raising questions about how quickly servers built on the same node—Clearwater Forest—can arrive in volume. Public reporting in recent weeks has described “lower-than-desired” yields and a company still working to hit year-end targets for volume. Intel maintains it will ship, but the path is narrower than investors hoped.

If 18A is the proving ground, 14A is the moonshot

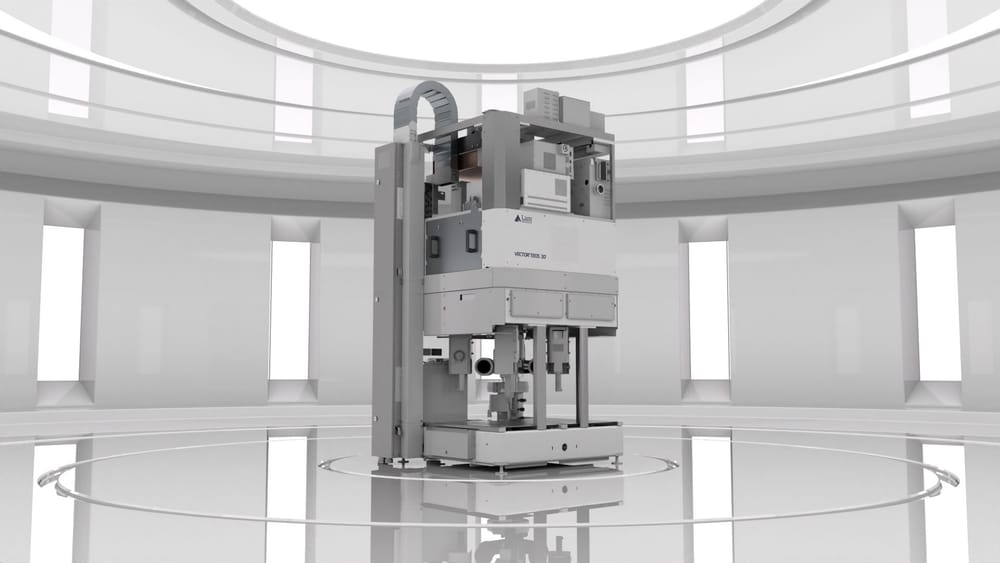

Intel has cast the follow-on node as its first designed around High-NA EUV, an ultra-precise lithography technology that can reduce the patterning complexity that has dogged recent manufacturing ramps. The catch is cost. Intel’s finance chief, David Zinsner, said plainly that 14A wafers will be more expensive than 18A, reflecting High-NA’s pricier scanners and retooled flows; the economics work only if the company lands “significant external customers” to anchor the node. In an SEC filing over the summer, Intel went further: if it can’t secure those anchor wins and meet key milestones, 14A “may not be economical” to pursue at full tilt. In other words, Intel will not overbuild capacity on spec again.

That newfound discipline has a political backdrop. In late August, Intel announced a deal to convert a chunk of promised CHIPS Act money into equity—roughly a 9.9% government stake—an arrangement the White House later described as still being finalized even as Intel said some cash had arrived. The structure is unusual for U.S. industrial policy and has already drawn scrutiny in Washington, but for Intel it provides runway: cash now, with strings attached in the form of governance and foundry-control provisions. It also heightens pressure to show progress on the very nodes that determine whether Intel can attract outside customers to its fabs.

The ripple effects of Intel’s push-pull are showing up across the chip ecosystem. Toolmakers that feed the cutting edge, such as ASM International, have blamed softer-than-expected logic/foundry orders on “timing,” a euphemism for big customers stretching out purchase decisions as roadmaps are revised. And this week, Synopsys—the design software and semiconductor IP heavyweight—saw its stock crater after reporting weakness in its Design IP unit tied to export restrictions and a “major foundry customer” that pulled back. Analysts widely read that as Intel, which has been a showcase for process-specific interface IP and physical libraries at 18A. When a foundry retimes its node or changes its product mix, suppliers feel it first.

The numbers behind Intel’s transformation help explain the tension. The company’s product businesses can still generate operating income, but Intel Foundry is deep in the red as it absorbs underutilized factories and invests for 18A and 14A. In the June quarter, Intel reported a multibillion-dollar operating loss for the foundry arm on a little more than $4 billion of revenue, a gap the company says should shrink as utilization rises and as it links new capacity to identified demand instead of hope. That is the logic behind pausing or slowing some previously announced projects and tying capital spending to customer commitments.

What happens next rests on three near-term proofs. First, Intel has to show that 18A can make real products at acceptable yields. Panther Lake in late 2025 into early 2026 and Clearwater Forest in 2026 are the bellwethers; if those ramps stabilize, confidence in Intel’s process and packaging combo—its RibbonFET transistors and backside power delivery—will rise. Second, the company needs to translate this week’s management changes into execution gains. The new Central Engineering group is designed to cut across silos and sell custom-designed parts to cloud and enterprise customers, which in turn could funnel foundry work back into Intel’s own fabs. Third, the company must produce tangible customer commitments for 14A, the node whose cost profile is only tolerable with anchor business. All three are necessary; none alone is sufficient.

Investors shouldn’t confuse a high-profile government deal and a fresh org chart with an industrial turnaround. The U.S. stake buys time, not execution. The leadership reshuffle resets accountability, but yields and design wins will decide the story. High-NA EUV gives Intel a potential technology lever that rivals are in no rush to adopt, yet it also raises the financial bar. If Intel can thread the needle—prove out 18A in volume, lock in early 14A partners, and make the custom-silicon business a real on-ramp for foundry customers—the company could finally stabilize the long slide in manufacturing credibility and turn its costly capacity into an asset again. If not, this year’s reset may be remembered as the moment Intel acknowledged that the future of cutting-edge chipmaking would be written somewhere else.

For now, the plane is still in flight, the parts are still being swapped, and the landing spot depends on customers who have more choice than ever. That’s what’s really going on at Intel.

Author

Investment manager, forged by many market cycles. Learned a lasting lesson: real wealth comes from owning businesses with enduring competitive advantages. At Qmoat.com I share my ideas.